It seems like just about everyone I know is finishing up a book-length project, which makes it the perfect topic for a blog post. But writing a book is a long process, so I figured I should probably keep it focused. For some reason, the title of Seth Fried’s book The Great Frustration popped into my head, and I figured frustration would be a great place to start.

So, I asked a few writers, including Seth, to discuss the most frustrating experience they had while writing their books–and how they overcame it. Here’s what my friend and former classmate Aubrey Hirsch said:

The most frustrating part of finishing my book was facing down my own self-doubt. After years of honing my ear and voice and painstakingly training my “inner editor” to notice when something in a story isn’t working, my inner editor started to go a little bit crazy. I finally felt like I had a complete short story collection, and suddenly nothing was right. My metaphors seemed overworked, my characters felt flat and my voice was just so…me. Luckily, a number of my artist friends had experienced similar crises of faith and they encouraged me take some deep breaths, trust in the skills I’d developed as a writer over the years, and tell my inner editor to shut the fuck up. It also helped to show the manuscript to some trusted friends and colleagues. Hearing their responses helped me look at the book with a fresh point of view and gave me the courage I needed to say “It’s done”!

One of my colleagues, Heather McNaugher, has a long-awaited poetry collection coming out soon. I’ve always been curious about the process of putting together a poetry collection. Regarding frustration, she said:

I have published a chapbook of poems, and in April my full-length book of poetry will be published by Main Street Rag Publishing Co. As far as completing and compiling a manuscript goes, in both cases I was my own worst enemy. You see, I refused to ask for help. I wrote in an attic, literally and metaphorically—in total isolation. This is not unusual for poets, but this romanticized version of the chain-smoking loner scribbling profound thoughts means death. Or, in my case, years of wasted postage and time. Take this last instance, with my forthcoming book, System of Hideouts.

At last after three years of writing and rewriting, I had 50 pages of poetry I knew to be stellar. I was especially attached to one poem, the one I read at every reading, the one I thought introduced readers to me in an alarming, authentic way. Now, in class after class, year after year, I tell students that if they are especially attached to a particular line or stanza or poem, it invariably needs to be mercilessly revised, if not cut altogether. How do I know this? From painful experience. I was a student myself once. But in the case of this poem, did I apply my tenet? No. Of course not. I made it the first poem of the manuscript, the poem that shook hands with no fewer than 25 editors of first book contests all over America (25 x 25 bucks a pop = $625.00).

I also insisted on titling the manuscript after a poem, a different poem, that people seem to like when I read at readings. A less interesting title by far, but I was, again, peculiarly convinced that it was the one.

A mentor of mine, Sheryl St. Germain, had offered for years to help me, and at last, literally three days before she boarded a plane for a semester-long sabbatical in France, I sheepishly placed the dejected beast under her door.

Sheryl made two recommendations: change the manuscript title, and swap the first poem for something less, uh, ferocious. The title, she explained, did not do justice to the overall arc of the book; and the first poem yanked us into pessimism, which undercut the project’s more engaging, hopeful message. That’s it. Literally two changes. Here I’d been so terrified, and so overwhelmed, by the prospect of feedback and its ensuing labor, that my solution was, RETREAT! Within three weeks of sending out the new version, I had a call that I was a finalist in MSR’s Editor’s Select Poetry Book Series, with the option to publish. Three weeks! It also ended up a finalist in two other contests.

Has she learned her lesson? Only the next project will tell.

And last but not least, Seth Fried had this to say:

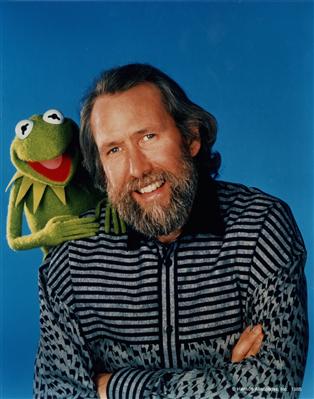

As a fiction writer, my interest has always been in short stories. So perhaps the most frustrating aspect of putting my first book together was the fact that publishers tend to be resistant to the idea of publishing short story collections. As my book was coming together, I spent a lot of time bemoaning the station of the short story. I was like a caricature of a disgruntled artist. I was impossibly bitter over the success of novels that I felt were mediocre when I saw so many talented short story writers (though I was thinking mostly about myself because I’m fairly self-important) struggle to get any traction whatsoever. What snapped me out of it was that one day I started to think about Jim Henson, who has always been a hero of mine… He created some of the most beloved and iconic art of the last century, and I doubt he accomplished that by sitting around and whining about how nobody likes puppets. He saw a medium that made sense to him and waded out into it with joy and enthusiasm and what seemed like an unflappable sense of self. The artists I love and admire are people who never depend on the norms of mainstream culture to determine how they are going to embrace their will to create. This realization has helped me to accept where short stories are at in our culture without any sense of resignation. In fact, I now feel compelled to be more urgent, joyful, and guileless in my efforts to make the kind of art that I want to make.

Special thanks to all the writers. I was really happy that Seth got back to me–otherwise, this blog post title wouldn’t have made much sense. (But I would have used it anyway.) Kind of like if John Malkovich hadn’t starred in Being John Malkovich. If you have frustrating experiences you’d like to share (preferably pertaining to writing), feel free to do so in the comments section below.

Aubrey Hirsch is the author of Why We Never Talk About Sugar (Big Wonderful Press, 2012). Her stories, essays and poems have appeared in literary journals both in print and online, including American Short Fiction, Third Coast, Hobart, PANK, and others.

Heather McNaugher is the author of System of Hideouts (Main Street Rag, 2012). She teaches poetry, nonfiction, and literature at Chatham University, and is poetry editor of The Fourth River. Her work has appeared in 5 A.M., The Bellevue Literary Review, New Ohio Review, Leveler, The Cortland Review, and on the radio show, Prosody. Her chapbook Panic & Joy was published by Finishing Line Press in 2008. She’s tried living elsewhere, but keeps coming back to Pittsburgh.

Seth Fried is the author of The Great Frustration (Soft Skull Press, 2011). His short stories have appeared in numerous publications, including Tin House, One Story, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Kenyon Review, The Missouri Review, and Vice, and have been anthologized in The Better of McSweeney’s, Volume 2 and The Pushcart Prize XXXV: The Best of the Small Presses.

Jim Henson photo from the University of Maryland.

I personally consider this amazing posting , “The Great Frustration:

Three Writers on Finishing a Book-length Project | Robert

Yune”, quite enjoyable plus the blog post was indeed

a good read. Thanks for your effort,Wade